A Brief History of Dore

And Ecgbert led an army to Dore

The written history of Dore can be traced back to the year 829 and an entry (wrongly recorded as 827) in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle - “And Ecgbert led an army to Dore against the Northumbrians and they offered him obedience and concord and thereupon they separated” and thus King Ecgbert became “Our Lord of the whole English speaking race, from the Channel to the Firth of Forth”.

The importance of Dore was its position on the boundary of the Anglo Saxon kingdoms of Mercia, recently conquered by King Ecgbert of Wessex, and Northumbria, the second most powerful kingdom. At the time, Northumbria was under pressure from viking raids and unable to fight on two fronts, leading to the acceptance of Ecgbert as overlord and effectively the first king of all England.

The event is commemorated on the village green by a gritstone monolith with a black granite plaque in the shape of a Saxon shield, appropriately emblazoned by a Wyvern, the war emblem of Wessex. The wyvern is still to this day established as the symbol of Dore, and is reflected in street names, also the names and logos of several local clubs and societies. Traditionally the meeting took place at Kings Croft next to the green, but in the event, the resulting unification did not last for long and Dore returned to its position as a rural backwater. The boundary between the two kingdoms, as marked by the local Limb (meaning limit or boundary) Brook, retained its significance however as the dividing line between Yorkshire and Derbyshire until 1934 and as the boundary between the Sees of York and Canterbury.

By the time of the Doomsday Book in 1085, the manor of Dore was just a small part of the holdings of a knight named Roger de Beusli, about whom we know very little. In 1183 the Premonstratensian order of monks founded Beauchief Abbey, just to the east of Dore, and the area become more prosperous, with the monks keeping sheep on the moors, and grinding corn at mills on the River Sheaf. Somehow Dore has managed to retain elements of its Derbyshire character, while benefitting from its proximity to Sheffield. Today there are still a number of old buildings in the village, mostly clustered within an easy walk of the church. What makes a village is its sense of community and the social occasions designed to reinforce this. Christmas was a major event in the calendar, but there were others such as the Dore Feast which took place on the Sunday following the 6 July and is still marked today by the annual Scout Gala, with its accompanying sheep roast. There was also a yearly ploughing match, now replaced by an annual Dore Show on the second Saturday in September, with horticultural, domestic and craft exhibits, proudly entered by villagers. Other occasions such as the Duke of Devonshire's Rent Feast in November have been overtaken by social changes.

Although well dressing takes place in the village during July, this is really an ancient custom from the limestone areas to the west of Dore, only introduced here in the 1950s. As an agricultural settlement, Dore was not so much a village as a collection of little knots of buildings linked by muddy tracks and open spaces, forming a network of greens that can now only be traced on old maps. All this was to change with the coming of the Dore Enclosure Act in 1822. The Duke of Devonshire, who had acquired the Manor of Dore in 1742, applied with other landowners for the enclosure of previously common land. The straight roads and resulting boundaries can be seen today. The Commissioners who made the awards also made provision for the common good, setting aside land whose rent would provide the salary of a schoolmaster.

A school and master already existed in the village, but those who had done well out of the Enclosure Act subscribed to a major extension. The Old School, as it is now known, was extended by public subscription in 1821 and served as the village school until the 1960s. The first significant schoolmaster at the new school was Richard Furness (1791-1857) who having been born in the Derbyshire village of Eyam, eventually settled in Dore in 1821, living in the house attached to the school. A man of many talents, he wrote letters for people, calculated their taxes, pulled their teeth, educated their children and represented the village on Parish business. Whether he was a good schoolmaster can be judged by a report from His Majesty’s Inspector who visited Dore in 1847. He found the children “dirty, many of them sitting without any means of employing their time and no check offered to their fighting and squabbling amongst themselves”. Richard died in 1857 and was buried at his insistence in Eyam Churchyard, but evidence of his talent as architect left a lasting legacy in the shape of Dore Church.

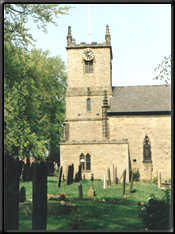

Christ Church Dore was built in 1828, although Dore did not become a separate parish until 1844. Gravestones all tell a tale, and those in Dore churchyard are no different. The churchyard catered for Dore and the local village of Totley, which did not gain its own church until somewhat later. Hence, we find the two communities separated on either side of the churchyard in death, as they were in life. Near the main road wall some small stones are tucked away, sadly recalling the itinerant ‘navvies’ and their families who died of smallpox during the digging of the nearby Totley Tunnel in 1893. This was a major engineering feat of its day, and at 3 miles 950 yards long is still the second longest tunnel in Britain. Dore has been lucky with its clergy up to the present day. Some have been real characters. One of the best anecdotes is about the Reverend Frank Parker who was preaching in the early 19th century, when two dogs entered the church and started fighting. Instead of having them put out he is reputed to have exclaimed, ‘Bet the black un’ll win!’

It is hard to imagine when walking around the area today, that it was in Dore and places like it that the industrial revolution began. Peak District lead had been smelted in the area since early times using wind blown furnaces on local hill tops, commonly recorded on maps as Bole Hill, and white coal (a form of charcoal) produced in the local forests. It was the introduction of water powered bellows which brought smelting into the valleys and the earliest record of water powered smelting in the country comes from this area. Soon, mills previously used for milling corn were converted to produce power for smelting, grinding, paper making and even to drive a rolling mill. Eventually every inch of local streams was harnessed for power, until coal and steam engines provided a more reliable source of power and industry moved east towards Sheffield and easier access to the sea. Even then, Dore did not become an industrial backwater and had a thriving coal and ganister mining industry right up until the Second World War. Abbeydale Hamlet, a grade 1 listed site and the birthplace of crucible steel as invented by Benjamin Huntsman in 1742, lies only just over the parish boundary and was no doubt built and manned by people from Dore. Certainly one of its managers lived within the village and was forced to reinforce his door with scythe blades as protection against his workers during the Sheffield Troubles.

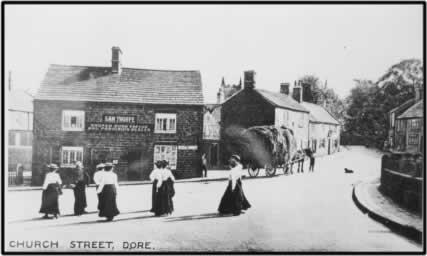

Looking back it is clear that the conversion to industry was a gradual process. People in Dore may have worked on farms or small holdings for part of the year, but many had other occupations as scythe smiths, miners, saw and anvil makers, button makers, file cutters and even a clockmaker. But it was the coming of the railroads in the late 1800's which finally set the seal on the shape of Dore today. Very quickly owners and managers of Sheffield factories realised they could live in comfort outside the smoke of the city, travelling in by rail from the newly built Dore & Totley station.

A new ‘Dore Road’ was built by the Duke of Devonshire connecting his village to the station, and along it Victorian villas spread, bringing new prosperity to the area. From then on the population pressures within Sheffield let inexorably to the urbanisation of the area, up to and into the 1960s. It was only the creation of Sheffield’s green belt which began to call a halt to this expansion, but not before the ancient heart of Dore had been swallowed up in commuter country.

Dore could so easily have become just another suburb of the city. Fortunately its discrete identity has been saved, firstly by the wedge of green belt comprising the historic Ecclesall Woods and Ryecroft Farm, secondly by the limits of the Peak Park and thirdly by a sense of community reflected in the work of the Dore Village Society and its battles to keep development in check.

Today Dore is a thriving community, which, added to its history and setting on the edge of the Peak Park, makes it well worth a visit, and for better reasons than King Ecgbert’s visit in 829!